Scholar Asti Hustvedt responds to Holobio, an inter-acting ecosystem by Nikima Jagudajev, Asad Raza and Ezra Fieremans held at Crush Curatorial (Amagansett) on September 15, 2018.

My work as a scholar involves research and close readings. I go back to my subject, usually a text, again and again, relying on the permanence of the page to corroborate or belie my initial reactions. Writing about the ephemeral Holobio after the fact is therefore a new and somewhat uncomfortable experience for me. Moreover, when I participated in the event, I had no idea that I would be asked to write about it. If I had known, I would have come armed with pen and paper to take notes, jotting down impressions and drawing diagrams--committing fleeting gestures to memory. However, had I known in advance, I would no doubt have missed out on the visceral magic I experienced as a body unburdened by a search for meaning.

What follows is an exercise in which I attempt to resist my usual tendency to explicate. Instead, it's an account of the traces Holobio has left in my memory and on my body, an account riddled with memory's inaccuracies and permutations. In other words, it is entirely possible that I am remembering what did not happen. I am, above all, an unreliable narrator.

I'll begin at the beginning. The entrance to the studio, an enormous potato barn that I have visited before, feels, for the first time, somewhat inhospitable, slightly treacherous. The lights are off and the steep staircase is covered in pine branches that partially obscure the steps. I worry I might slip. At the bottom of the stairs, a man--I later realized he was the artist Asad Raza--places hot sauce on my finger. Nothing about this gesture is exalted. Merely a drop from a small bottle squeezed on to my extended fingertip that I then place on my tongue. Yet, in the darkened space I experience it as a kind of eucharistic ritual, a hot sauce holy communion.

I enter the first chamber and unlike the darkened entryway, the space is airy and filled with natural light. A small group of adults and one little girl dance together. Their movements veer between the decidedly choreographed and the completely pedestrian. There are no playbills, no wall texts, no seating. There are no videos to watch, no paintings, drawings, photographs or sculptures to look at. I realize how much comfort I take in objects and the solitary contemplation of art and texts on walls. The conventions of performance, in which the performers remain safely sequestered on stage or, if it's an interactive piece, deliberately break the fourth wall to engage the spectators, are completely absent. This disruption of the usual customs is slightly unnerving for me: not the physical disquiet of perilous stairs and hot sauce encountered in the entryway but a social disquiet. Am I expected to stand and watch them? Staring seems like an invasion of privacy, yet walking past without looking also feels rude. My husband and I are alone in the room, and following his lead. I sit on the floor with my back against the wall and settle in to watch. The girl dances with intention, while the adults lounge on the floor, getting up from time to time to join her, oblivious to our presence. Our sitting causes no frowns, no officious guards scurry over to tell us we're breaking the rules. Two chords of music play repetitively, providing a minimal and quite beautiful sound backdrop. Evan, a friend, enters the room, wearing a white t-shirt. He is usually a collared shirt guy, and his attire only adds to my sense of displacement and unfamiliarity. He approaches and we engage in small talk. I have already been told that he is part of the performance, and our ordinary conversation confuses me. He moves on and I continue to turn my attention back to the dancers.

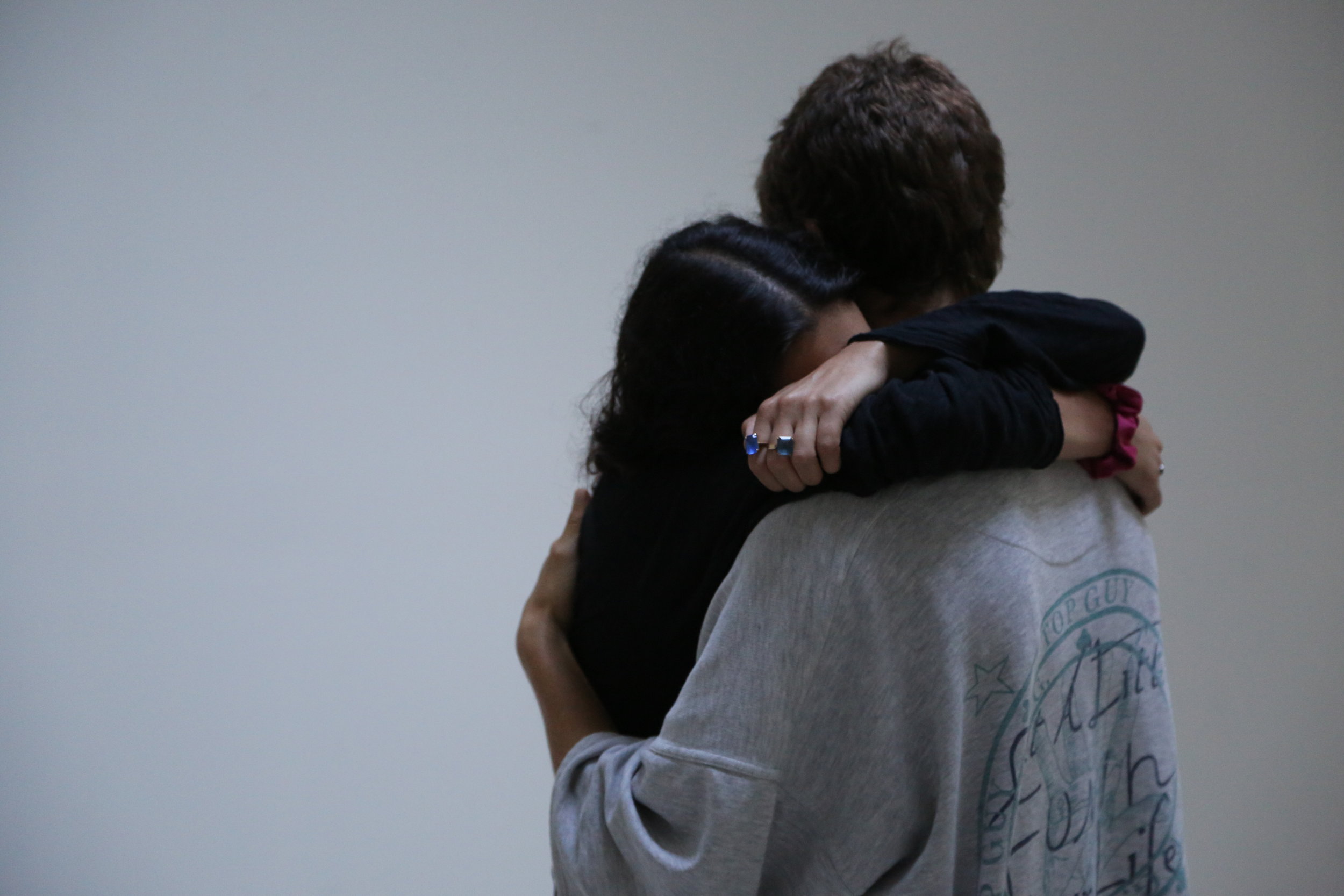

I wander into the cavernous second space and discover that the music is live, created by someone playing a piano at the far end of the room. The notes enter my body like a mantra as I watch a young man and a young woman slow dance. Evan is leaning dejectedly against one of the walls, hanging his head. My role is what? a spectator? a participant? a guest? an intruder? My husband approaches and wants to dance. I'm not sure if this is "allowed," but I agree, and we slow dance like two teenagers at a high school prom, integrating ourselves into the work of art.

I am happy to discover that the next space, just outside the studio door, has clearly articulated rules. Finally, I know what is expected of me. A sign posted to the fence that encloses the swimming pool and hot tub states: No clothing allowed on the other side. Before the boughs and the hot sauce, the dancers and my dancing, before normal Evan and dejected Evan, I would have interpreted this sign as a nod to 1970s hot tub hedonism, a hedonism that was decidedly not for me. Now, however, the command to get naked feels chaste, like the final stage in a rite of passage. I have already completed the earlier stages of a ceremony: the separation provoked by the darkened staircase, the initiation with hot sauce, the liminal inbetween-ness of the center rooms and I have emerged ready for my new status. The written sign with its clear instructions comes a relief, even though it demands nudity. For the first time since I entered Holobio, I know exactly what is expected of me. A burning fire, being fed sage or lavender or some kind of fragrant herb, only adds to the liturgical feeling. I strip down, weirdly unfazed by who might be seeing my middle aged body as I enter the hot tub, already populated by the mostly young and the firm. We sit together, climbing in and out of the tub and the swimming pool, in an atmosphere that is decidedly celibate, not Dionysian.

I must have lingered in the pool too long, because I completely missed the final act. Later on, at dinner, it is described to me, and in my imagination I experience it as a scene from a Bunuel film or a Beckett play. In the now darker barn, a tall performer who had shared the hot tub with me lumbers through the space slowly, wearing a bear suit, led by the artist. I may have invented this part, because I don't remember anyone telling it to me, but in my version he is on a leash, a frayed rope tied around his neck, Lucky being driven by Pozzo. Because the bear's head partially blocks his vision, he walks the expanse of the two rooms hesitatingly and at times comes close to stumbling, while the artist remains imperious. In any case, my imagined ending is decidedly abject. I stand and watch, dumbstruck, aching with the poignancy of the spectacle. In actuality, however, my experience of Holobio ends with me wrapped in a clean white robe. Memory is always, at least in part, a creative construction, a kind of storytelling that categorizes disparate parts, meaningless on their own, into a single narrative that takes on a life of its own, a holo bio, or whole life.

—Asti Hustvedt